Posts tagged ‘VE Day’

Why is May 8 a holiday in France?

Well, it is more precisely a solemn day of commemoration than a holiday, or a jour de fête. For May 8, 1945, is the day that Germany surrendered to the Allies, and Europe was at last free of the Nazi nightmare they had lived through for more than a decade.

Each year in towns, cities, and villages throughout France, this day is remembered. In my village of Essoyes there is always a défilé through the town, from the mairie to the war memorial next to the church, where an official proclamation is read. This year, on the eightieth anniversary of V-E Day, the proclamation was signed by Sebastien Lecornu, Minister of the Armed Forces of France, and Patricia Miralles, Deputy Minister.

Today our mayor read this proclamation to the people of Essoyes–young, old, and in-betweens–who had gathered to honor this day. This is an excerpt of what he read:

“…Le sacrifice pour la Victoire avait été immense. Aux soldats morts, blessés, prisonniers; aux résistants foudroyés ou torturés, s’ajoutaient les civils assassinés et déportés, en particulier les Juifs morts dans la Shoah, ainsi que les champs de ruines laissés par les durs combats de la Libération. La France était meurtrie, mais un peuple entier avait survécu à l’une des pires épreuves de son Histoire grâce au soutien de ses alliés…” (You can read the rest of the message here.)

Then the names of every citizen of Essoyes who had sacrificed his life during World War II were read aloud by children of the village, and the sapeurs-pompiers, who were carrying the flag and standing at attention shouted Mort pour la France after each name was pronounced.

After that we all proceeded to the monument aux morts, and from there to two streets in the village named in honor of André Romagon and Maurice Forgeot, local résistants who were murdered by the Gestapo. In each of these places a minute of silence was observed, and flowers were left.

The names of the individuals featured on this page–Louise Dréano, André Romagon, Maurice Forgeot, Howard Season, Dick Rueckert, Charles E. Anderson–are but a few of the brave souls–French, Americans, Canadians, and others from around the world–who risked their lives to deliver France, and ultimately Germany and the rest of Europe as well, from the terrible fascist regime that had terrorized this continent. Horrific loss of life and untold quantities of additional suffering were required to regain the freedom that was lost when that regime took hold.

Today’s proclamation from the French Minister of the Armed Forces concludes “In a world where threats are multiplying, where ancient threats hover again over the country, and while international relationships are being reconfigured, let us remember the sacrifices that an entire generation of Frenchmen and women withstood to liberate the country, to rebuild it, and to give us back our sovereignty….” (That’s my emphasis 😦 )

Would that the current threats to democracy and freedom that are hovering over us today, around the world, be pushed back without the need for such horrendous loss of life. So that we all might live better lives.

Is it too much to hope for?

Janet Hulstrand is an American writer/editor who lives in France. She is the author of Demystifying the French: How to Love Them, and Make Them Love You, and A Long Way from Iowa: From the Heartland to the Heart of France. You can also find her writing at Searching for Home.

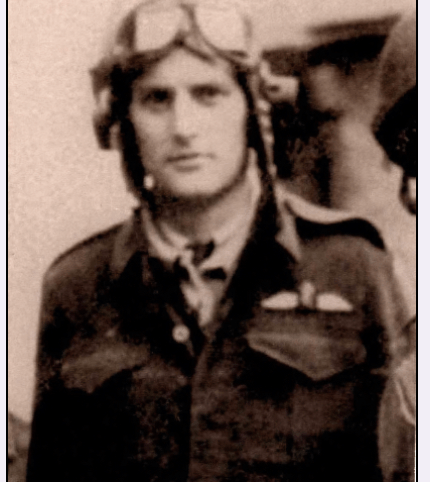

A Tribute to Flying Officer Charles E. Anderson: Pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force

Flying Officer Charles E. Anderson

Photo courtesy of Stephen Paul Garnier and AircrewRemembered.com

On May 8, 1945, in Berlin, the German Army surrendered to Allied forces, bringing World War II in Europe at long last to an end. This day is now known as V-E Day. In France, it is a national holiday, and a day of solemn commemoration. It is a day to remember and honor French men and women, as well as those from around the world who sacrificed their lives during the long struggle for freedom from Nazi Occupation.

The number of lives lost during that struggle, most of them young lives, is staggering. In the Battle of Normandy alone, which lasted from June 6-August 30, 1944, 73,000 Allied forces were killed and 153,00 wounded. About 20,000 French civilians were also killed during this battle, mostly during Allied bombings of French villages and cities.

Numbers of casualties in the thousands can sometimes dull comprehension of the countless individual lives lost. This post will honor the story of one young man—a brave and very capable Canadian pilot who played his part in freeing France from four years of Nazi Occupation, and paid the ultimate price. He is buried in a place of honor in a cemetery in southern Champagne—in the village of Essoyes, next to the war memorial.

***

Every year on May 8 in Essoyes, the village where I now live, there is a procession from the village square to the war memorial at the church, where a proclamation is read and the war dead are honored. Then, led by the mayor, members of the city council, and the volunteer firefighters, villagers proceed to the cemetery, where flowers are laid at the village’s other war memorial, and a minute of silence is observed to honor those buried there.

Similar ceremonies are held in towns, villages, and cities throughout France, and in Paris, in a televised ceremony, the president lays a wreath at the grave of the unknown soldier at the Arc de Triomphe.

One of the men buried in our village cemetery is Flying Officer Charles Edward Anderson, a native of Winnipeg, Manitoba, in Canada. Who was this young man who left a loving family and a safe life behind to venture into battle halfway around the world?

What follows is what I’ve been able to gather from Bill Kitson, Officer Anderson’s nephew, and Bill’s wife Rosemary Deans. Born after the war, Bill knows about his “Uncle Chuck” only through his mother’s memories of her beloved older brother, and Rosemary’s dedicated research into his story. Bill and Rosemary shared with me what they have been able to learn about Officer Anderson so I could write this tribute to his service.

As a young man, Charles Anderson wanted very much to serve in the war. When he was 19, he volunteered with the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the local Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve. His rank was recorded as “writer” and his trade as “stenographer.”

From there he requested a transfer to the Royal Canadian Air Force. Military records state that his interests were baseball and swimming, and his hobbies were stamp collecting and photography. It was also noted that after the war he wanted to remain with the RCAF, or become a commercial pilot. He was married and the father of a young child, a daughter who was 14 months old at the time of his death.

Charles Anderson and his bride-to-be in Winnipeg. Photo credit Sharon Merchant.

His training report indicated that he was “a good and capable pilot who [is] very anxious to start operational flying.” It also indicated that he was getting bored with the training and just wanted to get in on the action.

And he certainly did see action. On June 6, 1944 he and his squadron participated in one of the most dangerous, most costly, and most successful military operations in history: the D-Day invasion.

The report Officer Anderson filed after returning to England from that action gives a glimpse into just how complicated these situations were, and how much courage, sangfroid, and strategic thinking was required simply to survive:

I took off from Tarrant Rushton [England] at 0140 hours on 6 June 1944 on a special mission over France. After we had reached the target and completed our mission the aircraft was hit by flak and set on fire. I gave the order to abandon aircraft at approximately 0340 hours. All members of the crew got out successfully.

I landed in an orchard north of Bures, about 10 miles east of Caen. I hid my parachute, harness, and mae west, and lay in a bed of nettles throughout the day. I saw a number of German patrols.

At 2100 hours I made my way to a farm, where I was given food. I was then warned of an approaching German patrol, so I headed away from it in a southerly direction, accompanied by a Pole whom I had met at the farm. He indicated that he was a deserter from the German Army. After a time I left him and later met a party of British parachute troops. They took me to their Battalion Headquarters. I remained there that night and was sent to Divisional Headquarters next morning (7 June). I was taken to the beachhead in a car by a war correspondent and sent to the UK.

Two months later, on August 5, 1944, Officer Anderson’s plane again flew into France on a special mission. And his plane was shot down again—this time further into France, in southern Champagne. The bombing target Anderson was aiming for was northeast of Essoyes, between Noé-les-Mallets and Fontette. According to members of the crew, all of whom survived the crash, Officer Anderson’s courageous flying after the plane was hit saved their lives. He himself was killed in the crash, at just 22 years old.

Officer Anderson’s final, fateful mission took place in the midst of a confluence of events that took place in the area surrounding Essoyes in the first few days of August 1944, after the Germans had invaded a very large encampment of the maquis in the forest between Mussy-sur-Seine and Grancey-sur-Ource. There is much more story to tell about that day, and the days that followed. Much of it is told in the excellent Museum of the Resistance of l’Aube not far from here, in Mussy-sur-Seine. I have told bits of on this blog as well, and in future posts I will try to tell more.

The main thing to know is that after much more bloodshed, much more courage and suffering on the part of soldiers and civilians alike, this area was liberated. On August 27, three and a half weeks after the Maquis Montcalm was chased out of the forest near Mussy-sur-Seine by the Germans; three weeks after Officer Anderson’s plane crashed northeast of Essoyes; three days after a brutal massacre of civilians, including 20 children, in Buchères; and just one day after General De Gaulle led his triumphant march of liberation on the Champs Elysée in Paris, General Patton led the liberation of the city of Troyes, the capital city of this region; and the Allied forces continued on, through one more very tough winter, to push the Germans back, and eventually across the Rhine River.

There was a lot more fighting to do before victory would be declared by the Allies nearly a year later, on May 8. Every sacrifice made—by foot soldiers and airmen, by Allies and resistance fighters, as well as by civilians from many walks of life—and every act of courage carried out contributed to this final victory.

Needless to say, without these countless acts of courage, the history of France—and of the rest of the world—might have been quite different.

We all owe them all so much. I have just told part of one man’s story. There are so many more. So many more! They should not be forgotten.

Their courage, and their sacrifices, should never be forgotten.

Bill Kitson at his uncle’s grave in Essoyes, August 2006. Photo by Rosemary Deans.

Janet Hulstrand is an American writer, editor, writing coach, and teacher of writing and of literature who lives in France. She is the author of Demystifying the French: How to Love Them, and Make Them Love You, and A Long Way from Iowa: From the Heartland to the Heart of France; and coauthor of Moving On: A Practical Guide to Downsizing the Family Home.

Sources:

For numbers of casualties: https://apnews.com/article/d-day-invasion-normandy-france-nazis-07094640dd7bb938a23e144cc23f348c

For details about FO Charles E. Anderson:

https://aircrewremembered.com/anderson-charles-edward.html

https://www.pegasusarchive.org/normandy/charles_edward_anderson.htm

Private correspondence with William Charles Kitson and Rosemary Deans.

Re massacre in Buchères: