Posts filed under ‘About Essoyes’

Why is May 8 a holiday in France?

Well, it is more precisely a solemn day of commemoration than a holiday, or a jour de fête. For May 8, 1945, is the day that Germany surrendered to the Allies, and Europe was at last free of the Nazi nightmare they had lived through for more than a decade.

Each year in towns, cities, and villages throughout France, this day is remembered. In my village of Essoyes there is always a défilé through the town, from the mairie to the war memorial next to the church, where an official proclamation is read. This year, on the eightieth anniversary of V-E Day, the proclamation was signed by Sebastien Lecornu, Minister of the Armed Forces of France, and Patricia Miralles, Deputy Minister.

Today our mayor read this proclamation to the people of Essoyes–young, old, and in-betweens–who had gathered to honor this day. This is an excerpt of what he read:

“…Le sacrifice pour la Victoire avait été immense. Aux soldats morts, blessés, prisonniers; aux résistants foudroyés ou torturés, s’ajoutaient les civils assassinés et déportés, en particulier les Juifs morts dans la Shoah, ainsi que les champs de ruines laissés par les durs combats de la Libération. La France était meurtrie, mais un peuple entier avait survécu à l’une des pires épreuves de son Histoire grâce au soutien de ses alliés…” (You can read the rest of the message here.)

Then the names of every citizen of Essoyes who had sacrificed his life during World War II were read aloud by children of the village, and the sapeurs-pompiers, who were carrying the flag and standing at attention shouted Mort pour la France after each name was pronounced.

After that we all proceeded to the monument aux morts, and from there to two streets in the village named in honor of André Romagon and Maurice Forgeot, local résistants who were murdered by the Gestapo. In each of these places a minute of silence was observed, and flowers were left.

The names of the individuals featured on this page–Louise Dréano, André Romagon, Maurice Forgeot, Howard Season, Dick Rueckert, Charles E. Anderson–are but a few of the brave souls–French, Americans, Canadians, and others from around the world–who risked their lives to deliver France, and ultimately Germany and the rest of Europe as well, from the terrible fascist regime that had terrorized this continent. Horrific loss of life and untold quantities of additional suffering were required to regain the freedom that was lost when that regime took hold.

Today’s proclamation from the French Minister of the Armed Forces concludes “In a world where threats are multiplying, where ancient threats hover again over the country, and while international relationships are being reconfigured, let us remember the sacrifices that an entire generation of Frenchmen and women withstood to liberate the country, to rebuild it, and to give us back our sovereignty….” (That’s my emphasis 😦 )

Would that the current threats to democracy and freedom that are hovering over us today, around the world, be pushed back without the need for such horrendous loss of life. So that we all might live better lives.

Is it too much to hope for?

Janet Hulstrand is an American writer/editor who lives in France. She is the author of Demystifying the French: How to Love Them, and Make Them Love You, and A Long Way from Iowa: From the Heartland to the Heart of France. You can also find her writing at Searching for Home.

Springtime in Essoyes 2024

We are experiencing the fullness of spring these days. After a very rainy few weeks that was a bit too much of a good thing for the vignerons, and caused the river to be so full that it threatened to flood the center of Essoyes, finally the sun has come out, which is brightening spirits–and at least so far the river has stayed within its banks, pshew!

After all that rain, a little bit of sun has brought about abundant growth. The colza has shot up seemingly overnight (though not really), from knee-length to now over my head, and the fruit trees are in full bloom. How beautiful it all is!

Earlier this week I had the distinct pleasure–and honor–of meeting with a book group in Washington DC, to take questions about my memoir, A Long Way from Iowa: From the Heartland to the Heart of France, through the wonders of Zoom. The Women’s Biography book group sponsored by Politics and Prose, my favorite indie bookstore in the US, had chosen my book for their April selection, and wanted to know if I would like to visit their meeting.

I was delighted to do so even though for me that meant getting up at 1:00 in the morning so I could be awake enough to be coherent when I joined them at a little after 7:30 pm their time (and 1:30 am mine!). (Not being a night owl at all there was no way I would have been able to stay awake that long before joining them.) I think they had enjoyed the book (pshew again!) and they asked me such interesting questions and made wonderful comments. They even gave me permission to share a picture of our Zoom meeting so that I could encourage other book groups to do the same.

It is always SO NICE for authors to be able to meet directly with the people who read their books. So if you are reading this post, and you are interested in women’s memoirs, and you belong to a book group who might like to read my book, and have me visit your meeting, please do so! I’d love to have such an opportunity, and I think I have now proved my sincerity and willingness to get up at any hour of the day to meet readers. 🙂

Mother’s Day is coming up soon in both the US and France–and I think the UK and Canada also? And I think A Long Way From Iowa–as a three-generations-of-women fulfilling-the-dream story–is appropriate Mother’s Day reading. I hope some of you will agree.

Until the next post, happy reading (whatever you are reading). And happy spring!

Janet Hulstrand is an American writer, editor, writing coach, and teacher of writing and of literature who lives in France. She is the author of Demystifying the French: How to Love Them, and Make Them Love You, and A Long Way from Iowa: From the Heartland to the Heart of France; and coauthor of Moving On: A Practical Guide to Downsizing the Family Home.

July in Essoyes: Birthdays, Bicycles, and Champagne!

July has been a busy month for us in Essoyes. In mid-July, due to record-breaking temperatures, one of our sons decided that working from home in Essoyes was preferable to working from his apartment in Paris, so he and his girlfriend asked if they could come and stay with us for a few days.

Of course the answer was yes.

It was delightful to have them here. My son’s birthday is just five days before mine, and our dessert of choice for our birthdays is always a raspberry tarte (tarte aux framboises). Our patissier makes a wonderful tarte, and so we enjoyed one together a few days before his birthday.

Sometimes birthday celebrations can be frustrating to plan, especially with summer birthdays–getting everyone to be in the same place at the same being often challenging. This time we were very lucky to have all the stars line up so that an unplanned visit from two dear friends who live nearby coincided with our son’s unplanned escape from the heat wave in Paris, and voila! we had ourselves a delightful unplanned birthday party.

The last week in July began with a two-day birthday celebration for my birthday; first we had dinner at one of the two lovely riverside restaurants in the heart of Essoyes, the day before my birthday. Then we had dinner again the next day in the other one, when we realized that our other son, who lives in Lille, would be able to join us for that; and of course there was no better birthday present than to have him here.

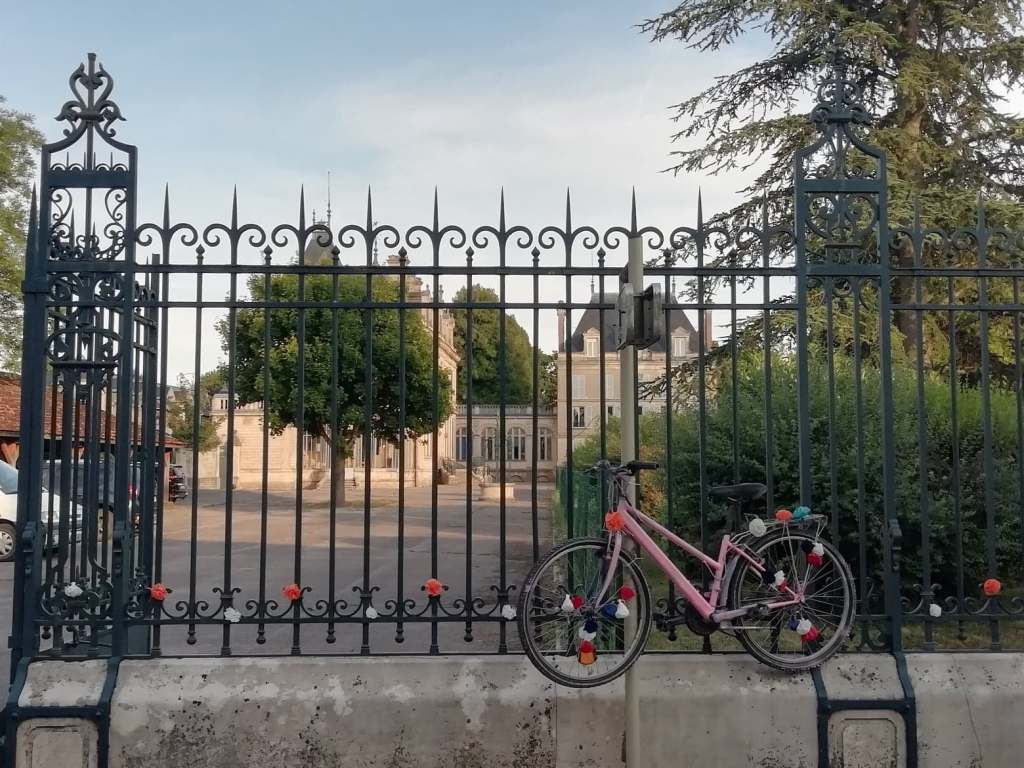

Then on Wednesday, July 27, the Women’s Tour de France came through town. There has only been a women’s race five times in the 113-year history of the Tour de France, and this was the first time in more than 30 years. According to the director of the race, it was a great success, with enthusiastic crowds greeting and cheering the cyclists on all along the 640-mile route.

In Essoyes, pink bicycles beautifully decorated with handmade crepe paper flowers, and crepe paper flowers gracing the grillwork and the bridges over the Ource River, helped point the way for the cyclists to make their several turns through town.

The Troyes to Bar-sur-Aube étape went right past our driveway as the cyclists came speeding downhill out of the forest, on the stretch from Gyé-sur-Seine to Essoyes. So we were the very first Essoyens to greet them with enthusiastic clapping and cheering as they entered our village. It was lots of fun; I hope they do it again next year. (Though if they do, they will no doubt take a different route: the Tour de France likes to spread the excitement to different villages and towns every year.)

The end of the week brought Son #1 and his girlfriend back to Essoyes, and this time a few of their friends also, who came to celebrate the Route du Champagne en Fête, an annual celebration in our department (l’Aube) of–yep, you guessed it–champagne!

We often feel like our swimming pool doesn’t get used enough; but the fun they all had in the late afternoon–swimming and sitting poolside, then hanging around talking, eating pizza, playing Uno, drinking ratafia until late in the evening–more than made up for some of la piscine’s more idle days.

And, as usual, evening fell with the gift of a very beautiful sunset.

Janet Hulstrand is a writer, editor, writing coach, and teacher of writing and of literature who divides her time between the U.S. and France. She is the author of Demystifying the French: How to Love Them, and Make Them Love You and is currently working on her next book, A Long Way from Iowa, a literary memoir.

Spring 2022 in Essoyes

Spring has been capricious this year. It was here, bringing sunshine, warmer weather, beautiful wildflowers, and sunnier dispositions. Windows were being opened to let warm breezes inside. Then it snowed again! Which was not good for the young buds on the vines that are so important to life here–and to making the champagne that brings pleasure to people far and wide. The temperature hit a record low for April, and so our local vignerons were once again desperately trying to save their crop of grapes for this year. 😦

Fingers crossed that winter–beautiful as it is–is done for this year! We’re all very ready for spring.

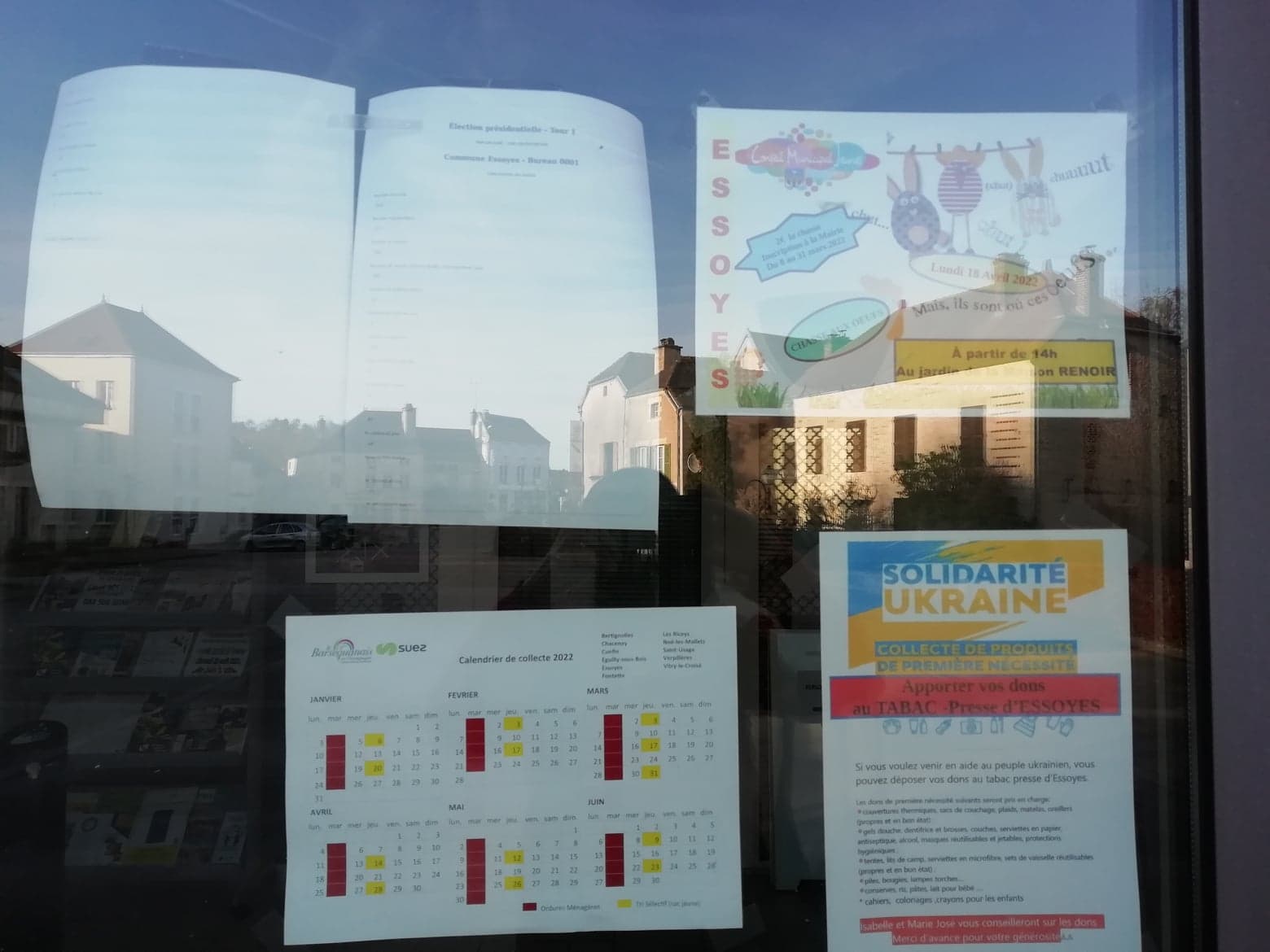

This is an important month in France, as voters choose their next president. In France there is a two-round system for the presidential elections. The two candidates who get the most votes in the first round–which was yesterday–then face off in the final election, which will be held on April 24.

This year there were 12 candidates on the ballot for the first round. And this year–as in 2017–the final choice for French voters is between Emmanuel Macron, the current president, and Marine LePen.

Although the system of counting votes here is very simple and old-fashioned –paper ballots are counted by hand in each commune or arrondissement–it seems to work better than the system in the US. By the morning after the election, sometimes even earlier, the results are posted so that everyone can see how their community voted. I walked into the village this morning so I could see the results for Essoyes posted at the mairie, but since you can’t read the figures on my photograph of the posting (instead you see a rather lovely reflection of the part of the village that was behind the photographer 🙂 ) you can see how Essoyens voted here if you’re curious. And you can read this very interesting article if you want to learn about part of what is at stake in this election. (Only part: there are always, of course, many many issues of concern. But this one seems pretty significant to me. )

The news from Ukraine continues to be horrifying, and the worst part of it is the slowness of action on the part of political leaders to take more vigorous and decisive action to deal with the rapidly mounting humanitarian crisis, and in fact a genocide. Another one. How can this be happening again. How can it?

Many are doing what they can–France, for example, has already taken in some 45,000 Ukrainian refugees since this crisis began less than two months ago. But there will surely be more tragedy ahead unless Putin’s war machine is stopped, and the powers that be are not doing enough, and they’re not acting quickly enough. They’re not!

Fossil fuels are destroying the planet and now they are also fueling this terribly bloody war. When will we put an end to this madness?! How many more innocent people have to suffer from our inability–or unwillingness–to change our ways? It is really so awful. So maddening. So disheartening. So wrong!!

There have been some bright spots in the news. Last week doctors and scientists around the world made clear where they stand about the climate crisis in large numbers. Thank God for them, for their dedication and honesty, for their commitment to doing what they can to turn things around before it is too late. If the climate action movement could pick up steam as rapidly as the resurgence of union activity seems to be doing in the United States as of last week, maybe things could begin to get better.

I hope so, and SOON! because really? Things are not going so well on Planet Earth right now. 😦

There is much hope to be found among youth around the world: young people with great courage, imagination, determination and generosity are doing what they can to correct the mistakes and make up for the negligence of their parents’ and grandparents’ generations. If you want to feel a little bit better about how things are going; if you wonder sometimes if there is any hope at all, you might want to read about some of these young people in this book. The young people featured in it are truly a source of great hope. But they need our help: they can’t solve these big problems alone.

Janet Hulstrand is a writer, editor, writing coach, and teacher of writing and of literature who divides her time between the U.S. and France. She is the author of Demystifying the French: How to Love Them, and Make Them Love You, and is currently working on her next book, A Long Way from Iowa: A Literary Memoir.

Late Summer, Essoyes 2021

Well, it has not been a quiet week in Essoyes, and next week will be even busier because I am told that is when the vendange will begin.

This is the week we (that is, our family) had to say goodbye to our beloved épicéas (spruce) trees, another victim of climate change. (Of course I am well aware that around the world, including in my beloved city of New York, others have suffered much worse fates, this very week. 😦 )

Nonetheless, for us this was a big loss, and it was a big job to take these trees down. Fortunately, we were able to call upon our local paysagiste, one of whose specialities is “abbatage délicat,” to take on this enormous task. And délicat is indeed the right word for the work they did for us this week.

We were most impressed (plus relieved) to watch this team practice their expertise. Five (out of the 32 very tall trees that had to come down) were right next to our house, with a fence behind them, and a road on the other side of the fence, plus a farmer’s field. These guys–two guys, one with a ladder and a chain saw, the other standing at a distance with a rope attached to the tree–managed to take these huge trees down, one at a time, in such a way that when they came crashing down, they cleared the house by a very narrow margin, and also managed to not hit my beloved “Christmas tree”–a beautiful, majestic cedar, which is (thankfully) immune to the insects that have devastated all the spruces. This task was carried out with surgical precision. It was amazing!

And it was not a lucky accident that it turned out that way. This was the result of sheer professional expertise. I have often remarked on the excellence of the French in mastering their various métiers. Here again we saw that excellence demonstrated.

So while it was sad to see our lovely trees go, remembering how that line of evergreens had sheltered, more or less cocooned us here in our lovely French home, by the time we were able to arrange to have them taken down, we were not only ready, but actually quite eager, to have it happen. Because by the time they came down, they had not been green in the least for a good while; and there is really nothing at all lovely about looking at a line of dead trees. (It’s also no fun wondering every time a storm comes up which of them may come crashing down, and where!)

And so, in the end, the new and expansive openness of our view from here has felt liberating, even kind of joyful. The beauty of the sunsets that I have so often shared on my Facebook page no longer have to be taken while standing between the trees and holding my camera up: the view of that beautiful sky and the fields over which it performs its daily visual splendor now can be seen clearly right from our house, and all around our yard.

In other news: French kids went back to school this week. And I must say, this tweet, with a short video of the rentrée, which I saw on the news feed of L’Est Eclair (our regional newspaper) really touched my heart. I feel for all the parents, kids, teachers, and school administrators who are doing their best both to resume a semi-normal school year, and to protect the kids from that nasty virus. It’s not easy. I hope things will go well. The kids didn’t ask for this, and they don’t deserve it. 😦

Anyway: as the virus picks up in various places, these words again become very useful: wear your masks, wash your hands, practice those rules of social distancing. Be safe, be well. Prenez soin de vous…

Janet Hulstrand is a writer, editor, writing coach, and teacher of writing and of literature who divides her time between the U.S. and France. She is the author of Demystifying the French: How to Love Them, and Make Them Love You, and is currently working on her next book, A Long Way from Iowa: A Literary Memoir.

Summertime 2021

In spite of early predictions for another hot, dry (meaning good-for-wasps) summer, at least in this corner of southern Champagne it has been cool and frequently rainy. I’m not sure what this means for the farmers around here: I know the season started out badly for those who grow grapes and other kinds of fruit, due to a few unseasonably warm days in May, followed by a late freeze.

To the untrained eye, the vineyards look healthy, at least the ones I have seen. In any case, my message to the world is the same as it always is: buy champagne! Support farmers!

And my message to wasps is: no offense, but we have not missed you this summer!

I thought that in this post, rather than try to sum up the ever-changing rules, progress in the fight against Covid, sliding back in the fight against Covid, disagreement about how to handle the pandemic, etc., I would give you some respite from all that, through a little late-summer photographic resume of this beautiful part of the world in which I find myself.

Fields of wheat, vineyards

Poppies can grow anywhere!

The fertile, rolling hills of Champagne

Wind turbines on a plateau. Clean, sustainable energy!

These field flowers were luminescent even at dusk.

The photo at the top of this post was taken at dawn. And the one below, at dusk.

There is no such thing as a day here that is not beautiful. I hope wherever you are, you will find beauty in your world too, even if it is in the lovely colors of sunset saturating a brick wall in golden light, or reflected in panes of glass. Or wildflowers making their determined way through cracks in a sidewalk, or a pile of gravel. There’s beauty everywhere…

Stay safe, stay well everyone. Get the vaccine. Wear those masks. So much to enjoy in this world.

Janet Hulstrand is a writer, editor, writing coach, and teacher of writing and of literature who divides her time between the U.S. and France. She is the author of Demystifying the French: How to Love Them, and Make Them Love You, and is currently working on her next book, A Long Way from Iowa: A Literary Memoir.

Midsummer Night’s Dream…

It is just past summer solstice, and France is creeping out from under the restrictions imposed due to the pandemic. Last week Prime Minister Jean Castex announced that people are no longer required to wear masks outdoors. (This included, significantly, children playing in the school playgrounds; one can only imagine the happiness of the little ones at this news.)

Also, the evening curfew has been lifted completely. This came just in time for the annual Fêtes de la Musique, a nocturnal festival that occurs all over France on the summer solstice, and is followed by the celebration of the Festival of St. Jean, on June 24.

Here in Essoyes, people are joyfully celebrating the ability to be together again. The restaurants and cafes have reopened. A couple of weeks ago there was a village-wide vide maison (empty the house) what we would call a garage or yard sale, and other special activities, including a hike followed by a community picnic.

Reopening means reopening cultural events also. There will be organ concerts in the church at Essoyes over the next few weeks, bringing musicians from as near as Dijon, and as far away as Scotland and Finland.

Among the benefits of country living are being able to get your second Astra Zeneca dose from your friendly local pharmacists, which I did last week. At this point about 50 percent of the French population has received a first dose of the vaccine, and 30 percent have received their second: it’s not enough, but it’s a good start. Hopefully the numbers will continue to grow as rapidly as possible. Last week the vaccine was opened up to children 12 and older as well.

The abundance of the land begins to express itself in early summer. Here are a few proofs of that.

These images are of the barley, wheat, and wild strawberries that grow right in or next to my yard. Up in the hills surrounding the village, the vignerons have been especially busy over the last 10 days: this is the part of the summer where the vines must be trellised, which requires extra hands in the vines. The enjambeurs have been heading into the vineyards early in the morning–sometimes at dawn. Of course, this being France, they come back down for a nice, long lunch. Then it’s back into the vineyards again to work until early evening.

I am lucky to have a neighbor whose hens are prolific enough that she is able to share their eggs with others. Fresher, more delicious eggs I have never tasted!

Finally, from spring to fall there are many lovely varieties of wildflowers here that spring up of their own volition, brightening landscapes and cityscapes alike with their colorful variations. Here are a few of the current stars of the show.

Wishing you a safe, pleasant summer wherever you are. Bonne continuation, et prenez soin de vous!

Janet Hulstrand is a writer, editor, writing coach, and teacher of writing and of literature who divides her time between the U.S. and France. She is the author of Demystifying the French: How to Love Them, and Make Them Love You, and is currently working on her next book, A Long Way from Iowa: A Literary Memoir.

Adieu to a Much-Beloved Village Doctor

I knew fairly early a few mornings ago that someone in our village must have died, because the way the church bells rang at 8:00 was not the usual way. They were tolling, not just ringing the hour.

So I checked the Facebook page for our village, and that is how I learned that the person who had died was Dr. Grizot, and that there would be a funeral mass for him held in our village church that afternoon.

Essoyes is lucky to have a village doctor. Many communities in rural France do not have doctors living in their communities. We have one now, and we were also lucky to have had Alain Grizot as our village doctor for many years, until he retired a few years ago.

I didn’t know Dr. Grizot very well, but I knew him a bit, because several times he was the doctor who cared for members of my family. I also encountered him several times after his retirement, at cultural or heritage events that he was participating in, and so was I. One was the annual memorial hike led by Guy Prunier, in honor of the French Resistance unit, the Maquis Montcalm, based in nearby Mussy-sur-Seine. Another was a guided walking tour led by the staff of the Maison Renoir here in Essoyes.

A few years ago I asked Dr. Grizot if he would be willing to sit down with me and answer some questions about his career as a village doctor. It was my intention to publish the interview on this blog but I was not able to do that, mainly because the interview was very long, and in French (so it required transcription and translation, both very time-consuming tasks), and thus difficult for me to find the time to do it. And now, sadly, I don’t even have access to the recording because it has become locked in an old computer that I can’t get into anymore. (This made me sad before every time I thought about it, and it makes me even sadder now. ) If I can find a way one of these days to recapture that interview, I will eventually do what I intended to do in the first place: which was to publish it as one of a collection of occasional essays and interviews I am posting, as I am able to do so, to feature the lives and the work of some of the citizens of this town, and their contributions to the life here.

However, I do remember a few things from that interview that I can share here. I remember that although he came here, I believe as a young man, a new doctor, and then spent the rest of his life here, he was not born and raised in Essoyes. I vaguely remember him telling me that he came from somewhere in Burgundy, a fact that seems to be confirmed, or at least strongly suggested, by the fact that he was to be buried in Nolay, a village south of Dijon. I remember also that I asked him what was the hardest thing about being a doctor. And while I can’t remember his exact words, I remember that before he answered he looked both thoughtful and sad, and that he said something about how hard it was to see people who he had cared for as little children die as young adults. I believe he said something specifically about car accidents.

Village doctors, and family doctors in general, are becoming more and more rare individuals in our modern world. The amount of training required is considerable, it is ongoing, and the compensation is not what it should be, certainly not comparable to the compensation specialists can expect to receive. Though in general health care in France is much better than in the U.S., this is a problem here just as it is in the United States. I think we talked a bit about this too, about how hard it was to have enough doctors when the sacrifices asked of them are as great as they are, and the rewards insufficient for all but the most dedicated, and those able to survive on the very modest amounts they are allowed to charge for their services.

We did discuss this a bit, but it was in the context of how this a problem not so much for doctors (though it certainly is that), but for the public. What I remember most about that interview was Dr. Grizot’s intelligence; the way he spoke about current and evolving medical issues knowledgeably and with genuine interest, even though he was retired from the profession. He talked for a long time, and seemed to be very happy to have been asked to talk about his work. The other thing that stood out was his compassionate nature, which was evident as he talked about the people he had cared for. That is what seemed to matter the most to him.

So, I would say that one way to honor Dr. Grizot is to remember how much he cared. And to do what he would want. I think he would want everyone to take good care of themselves (“prenez soin de vous“), to carry out, as it were, the work that good doctors everywhere do when they take care of us.

And to drive carefully. An especially good time of year to remember these things.

Janet Hulstrand is a writer, editor, writing coach, and teacher of writing and of literature who divides her time between the U.S. and France. She is the author of Demystifying the French: How to Love Them, and Make Them Love You, and is currently working on her next book, a literary memoir entitled “A Long Way from Iowa.”